PYTHON: Feeding in acute pancreatitis

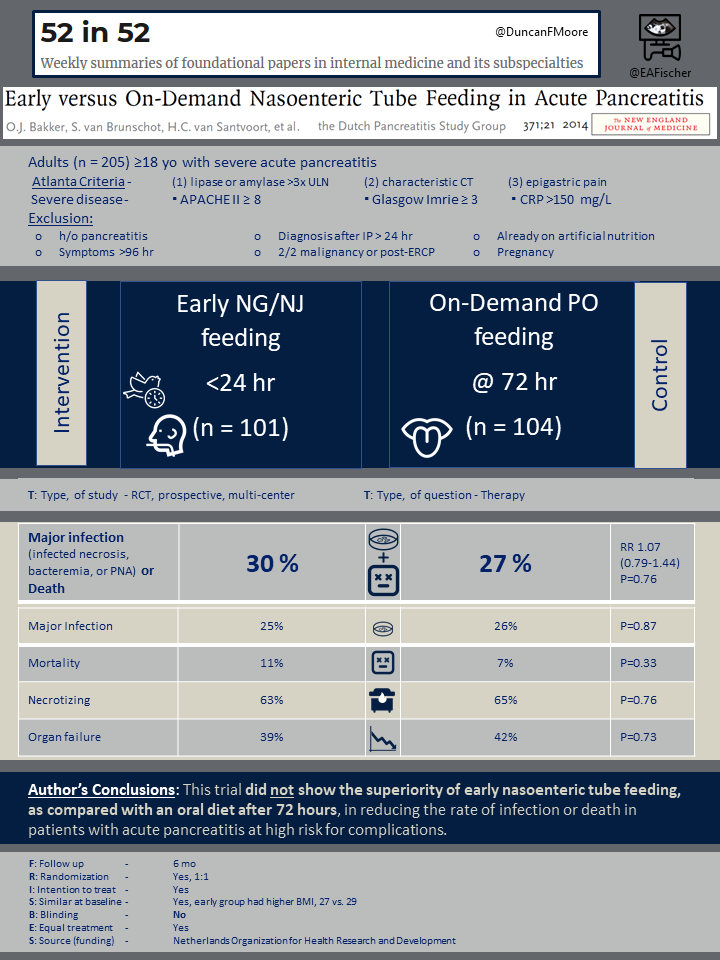

Early versus on-demand nasoenteric tube feeding in acute pancreatitis.

Bakker OJ, van Brunschot S, van Santvoort HC, et al. for the Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group.

N Engl J Med. 2014 Nov 20;371(21):1983-93. [Full text]

Acute pancreatitis is the most common gastrointestinal cause of hospitalization and can be classified by mild, moderate, or severe disease. It is believed that in pancreatitis there is increased mucosal permeability and decreased intestinal motility allowing for bacterial translocation, which increases the risk of infections [1]. It was theorized that feeding would stimulate the already inflamed pancreas and that bowel rest was preferred until the abdominal pain had improved [2]. More recent studies have shown that early enteral nutrition (started within 48 hours) can decrease the risk of infection [3,4].

At the time of publishing of the PYTHON trial there were mixed guidelines regarding timing of feeding in pancreatitis. General consensus of international guidelines recommended that for severe pancreatitis early nutritional therapy be initiated; however, in mild to moderate cases, nutritional therapy was recommended only if anticipated NPO for 5-7 days was anticipated – a finding that likely could not be determined until 3-4 days into hospitalization [5].

The PYTHON trial aimed to determine if there was any benefit to initiating early nasoenteric feeding (<24 hours) compared to an oral diet at 72 hours.

Population

This study included six university medical centers and 13 large teaching hospitals of the Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Adults (>18 years old) who were admitted for their first episode of acute pancreatitis defined by at least 2 Atlanta criteria (see below) and anticipated to have severe disease were included in the study.

Atlanta Criteria for acute pancreatitis

(1) serum lipase or amylase >3 times upper limit of normal

(2) characteristic findings on CT, and

(3) epigastric abdominal pain

Severe disease was classified as APACHE II score ≥ 8, Glasgow-Imrie score ≥3, or CRP > 150mg/L. Exclusion criteria included those with history of pancreatitis, symptoms onset >96 hours prior to presentation, diagnosis that occurred either 24 hours into admission or intraoperative for acute abdomen, etiologies related to malignancy or post-ERCP, those already on artificial nutrition (enteral or parenteral), or pregnant women.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study included major infection (such as pancreatic necrosis, bacteremia, pneumonia) or death within 6 months of randomization.

Important secondary outcomes included the individual components of the primary outcomes as well as development of necrotizing pancreatitis and new onset organ failure.

There was an additional subgroup analysis performed restricted to those with APACHE II score 13 or higher. Additional post hoc analyses were performed for those who met SIRS criteria (due to increased risk of complications) and one based on BMI (as this had differed between the two treatments groups).

There were no safety outcomes reported.

Results

Between August 2008 and June 2012, 867 patients were screened. A total 205 patients were randomized into 2 groups: 101 patients were started on tube feeds within 24 hours from randomization (early group) and 104 patients were started on oral diet 72 hours after admission (on-demand group).

Those in the on-demand group were allowed to eat before the 72 hour mark if they requested for food. If they were not able to tolerate oral feeds at 72 hours, nasoenteric feeds were started instead.

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups with exception of BMI, with the early group having average BMI higher than on-demand group (29 vs 27, p=0.01). In the on-demand group, 31% of patients required nasoenteric tube feeding at 72 hours. Fiver percent of patients in the on-demand group requested and received food prior to the 72 hour mark.

At 6 months, there was no difference in rate of severe infections, death, or the composite of those two outcomes. Thirty percent (30%) of patients in the early group vs 27% in the on-demand group had either major infection or death (RR 1.07, CI 0.79-1.44, p=0.76). Twenty-five percent (25%) of patients in the early group had major infections, similar to the on-demand group who has 26% with major infection (p=0.87). Mortality rates also did not significantly differ with rates of 11% in the early group and 7% in the on-demand group at 6 months (p=0.33).

There were no significant differences in secondary endpoints between the two groups. Sixty three percent (63%) of patients in the early group had necrotizing pancreatitis compared to the 65% in the on-demand group (p=0.76). Thirty-nine (39%) of patients developed single organ failure in the early group which is similar compared to the 42% in the on-demand group (p=0.73). A small percentage of patients also developed multiple organ failure (defined as two or more organs failing in the same day and lasting more than 48 hours) with 10% in the early group and 8% in the on-demand group (p=0.77).

Additional subgroup analysis of patients with APACHE II score of 13 or higher did not show a significant difference in death and severe infections between the two groups. Post hoc subgroup analysis for those who met SIRS criteria as well as those with BMI less than 25 and greater than or equal to 35 did not show a significant difference in death and severe infection as well.

Discussion

This pivotal study included a sizable number of patients across multiple healthcare facilities that specifically studied timing of nutrition in patients with acute pancreatitis. Although prior studies, not specific to pancreatitis, had suggested initiating early feeding decreases rate of infection, PYTHON did not find a significant difference for acute pancreatitis. This finding could partly been due to an insufficient sample size. The study fell short of the estimated 208 patients to achieve a power of 80%. While guidelines at the time had already recommended early tube feeding in severe pancreatitis and mixed guidelines in mild to moderate disease, PYTHON excluded mild and moderate acute pancreatitis when comparing early versus delayed feeding.

This trial also used three different scoring systems to identify severe pancreatitis: APACHE II, Glasgow-Imrie scale, and CRP. However, most scoring systems require data through 48 hours to provide a more accurate prediction. APACHE II was initially created to evaluate severe disease in the ICU setting but does have good sensitivity and specify when applied to acute pancreatitis outcomes. CRP and Glasgow-Imrie scoring do not provide good sensitivity (44.4% and 73.5% respectively) or specificity when applied in the first 48 hours [6]. Therefore there may be limitations in the severity of disease classification in PYTHON.

Ever since PYTHON was published in 2015, additional randomized controlled trials have been conducted to further assess the timing of feeding in acute pancreatitis. Notabley, a metanalysis of 11 randomized trials comparing early (within 48 hours) versus delayed feeding in acute pancreatitis also did not find a significant change in mortality between early and delayed feeding [7]. For mild to moderate acute pancreatitis, length of hospital stay was decreased in 4 of those studies.

While there does not seem to be a difference in mortality between early vs delayed feeding, delayed feeding is still associated with increased risk for infected peripancreatic necrosis, multiple organ failure, and total necrotizing pancreatitis. The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) guidelines recommend initiating oral feeding within 24 hours. While oral feeds are preferred, in cases where patients cannot tolerate feeding, nasoenteral feeding can be pursued [8].

| F: Follow up | 6 mo |

| R: Randomization | Yes |

| I: Intention to treat | Yes |

| S: Similar at baseline | Yes, though early group had higher BMI, 27 vs. 29 |

| B: Blinding | NO |

| E: Equal treatment | Yes |

| S: Source (funding) | Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development |

Summary by Michelle Punzal, MD

References

- Dervenis, C., Smailis, D., & Hatzitheoklitos, E. (2003). Bacterial translocation and its prevention in acute pancreatitis. Journal of hepato-biliary-pancreatic surgery, 10(6), 415-418.

- Banks, P. A., Freeman, M. L., & Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. (2006). Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG, 101(10), 2379-2400.

- Blaser, A. R., Starkopf, J., Alhazzani, et al. (2017). Early enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: ESICM clinical practice guidelines. Intensive care medicine, 43(3), 380-398.

- Marik, P. E., & Zaloga, G. P. (2001). Early enteral nutrition in acutely ill patients: a systematic review. Critical care medicine, 29(12), 2264-2270.

- Mirtallo, J. M., Forbes, A., McClave, et al., & International Consensus Guideline Committee Pancreatitis Task Force. (2012). International consensus guidelines for nutrition therapy in pancreatitis. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 36(3), 284-291.

- Simoes, M., Alves, P., Esperto, H., et al., J. N. (2011). Predicting acute pancreatitis severity: comparison of prognostic scores. Gastroenterology research, 4(5), 216.

- Vaughn, V. M., Shuster, D., Rogers, et al.. (2017). Early versus delayed feeding in patients with acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Annals of internal medicine, 166(12), 883-892.

- Crockett, S. D., Wani, S., Gardner, et al.. (2018). American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on initial management of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology, 154(4), 1096-1101.