Combination Therapy for AML

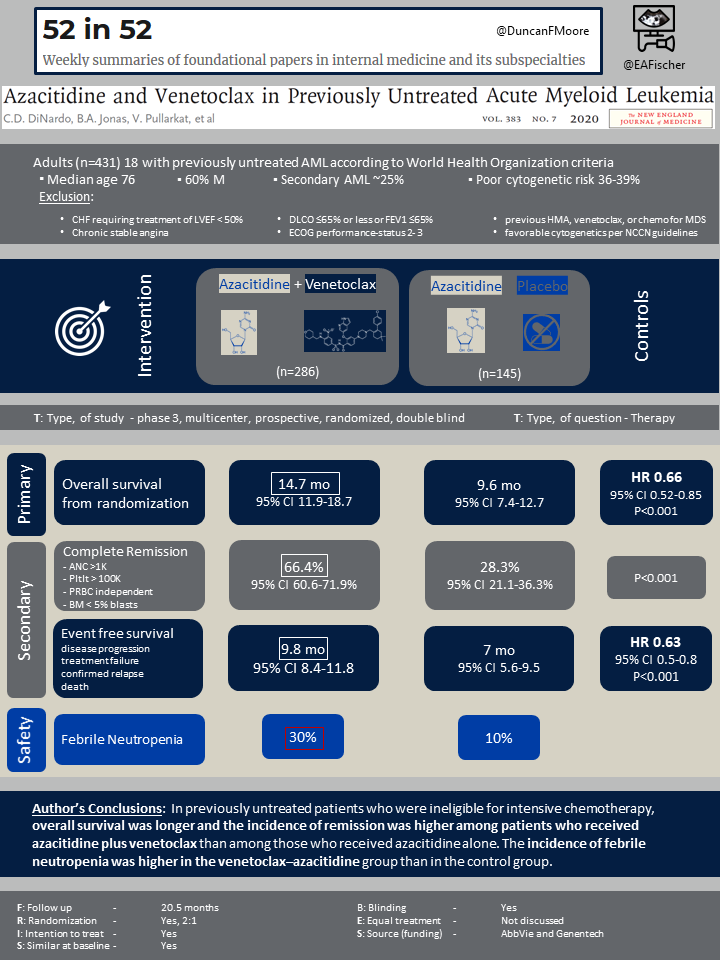

Azacitidine and Venetoclax in Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukemia.

DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, Tet al.

N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug 13;383(7):617-629. [Full Text]

Summary by Xinyu von Buttlar

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogeneous hematologic malignancy characterized by the clonal expansion of myeloid blasts in the peripheral blood, bone marrow, and/or other tissues/organs1, as defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. It is the most common form of acute leukemia diagnosed in adults, with the median age at diagnosis being 68 years (54% diagnosed at 65 years or older), according to the SEER Cancer Statistics Review2. More importantly, approximately a third of AML patients are ≥75 years at the time of diagnosis2. Due to advanced age, coexisting conditions, and higher comorbidities, this patient population candidacy for intensive chemotherapy can be limited.

Until recently, therapeutic options for these patients included low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) or the hypomethylating agents (HMA) azacitidine and decitabine, which have historically provided only modest benefits3. Azacitidine monotherapy has been associated with an incidence of remission of only 30% or less and survival of less than 1 year4. Venetoclax is a selective oral small-molecule B-cell leukemia/lymphoma-2 (BCL2) inhibitor and has been shown, in a phase 2, single-arm study, to induce apoptosis in malignant cells in patients with relapsed/refractory AML or those who could not receive intensive chemotherapy5.

In a phase 1b study in untreated patients with AML who were ineligible for intensive chemotherapy and lead by CD DiNardo et al., the combination of azacitidine and venetoclax led to complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery in 71% and a median 21.2 months duration of response6. The purpose of the summarized study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety (phase 3) of the combination of azacitidine and venetoclax, as compared with azacitidine and placebo, in previously untreated patients with AML who were ineligible for intensive induction chemotherapy.

Population

This study screened 579 patients, among which 433 underwent randomization, and 431 were included in the intention-to-treat population. Key eligibility criteria included an age of 18 years or older and a confirmed diagnosis of previously untreated AML according to World Health Organization criteria.

Patients were ineligible for standard induction therapy if:

- ≥75 years old

- CHF requiring treatment of LVEF < 50%

- chronic stable angina

- DLCO ≤65% or less or FEV1 ≤65%

- ECOG performance-status score of 2 or 3

- previous HMA, venetoclax, or chemotherapy for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)

- patients with a favorable cytogenetic risk according to the NCCN guidelines.

This study used 2:1 randomization: 286 patients were assigned to azacitidine plus venetoclax, and 145 patients were assigned to azacitidine plus placebo; among them, 283 and 144, respectively, received treatment and were included in the safety analysis. In both groups, the median age was 76 years, and 60% of the patients were male. Secondary AML was reported in 25% of the patients in the azacitidine plus venetoclax group and in 24% of the patients in the control group, and poor cytogenetic risk was reported in 36% and 39%, respectively. Nearly half the patients, 141 (49%) in the azacitidine plus venetoclax group and 65 (45%) in the control group, had at least two reasons for ineligibility for intensive therapies.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was overall survival, which was defined as the number of days from randomization to the date of death. The secondary outcomes were composite complete remission (complete remission or complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery), complete remission with or without partial hematologic recovery, complete remission by the initiation of cycle 2, red-cell and platelet transfusion independence, composite complete remission and overall survival in molecular and cytogenetic subgroups, event-free survival, measurable residual disease by flow cytometry, and quality of life according to patient-reported outcomes.

Complete remission was defined as an absolute neutrophil count of more than 1000 cells per cubic millimeter, a platelet count of more than 100,000 per cubic millimeter, red-cell transfusion independence, and bone marrow with less than 5% blasts. Complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery was defined as all the criteria for complete remission, except for neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count, ≤1000 per cubic millimeter) or thrombocytopenia (platelet count, ≤100,000 per cubic millimeter). Complete remission with partial hematologic recovery was defined as all the criteria for complete remission, except that both the neutrophil and platelet counts were lower than the threshold designated for complete recovery (for neutropenia >500 per cubic millimeter and a platelet count of more than >50,000 per cubic millimeter). Event-free survival was defined as the number of days from randomization to disease progression, treatment failure (failure to achieve complete remission or <5% bone marrow blasts after at least six cycles of treatment), confirmed relapse, or death. Transfusion independence was defined as the absence of a red-cell or platelet transfusion for at least 56 days between the first and last day of treatment. In patients who had composite complete remission, measurable residual disease was assessed by flow cytometry, with negativity defined as less than 1000 aberrant blasts. Quality of life was assessed with the use of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Fatigue SF7a patient questionnaire and the Core Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer C30.

In the azacitidine plus venetoclax group versus the control group, 120 patients (42%) and 62 (43%) had disease progression or morphologic relapse. The most common reason for discontinuation during the follow-up for survival was death (161 or 56% in the azacitidine plus venetoclax group and 109 or 75% in the control group).

Results

Primary outcome

The median overall survival was 14.7 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 11.9 to 18.7) in the azacitidine plus venetoclax group and 9.6 months (95% CI, 7.4 to 12.7) in the control group (hazard ratio for death, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.85; P<0.001).The median duration of follow-up was 20.5 months (range from <0.1 to 30.7).

Secondary outcomes

Composite complete remission was achieved in 66.4% (95% CI, 60.6 to 71.9) of the patients in the azacitidine plus venetoclax group and 28.3% (95% CI, 21.1 to 36.3) of the patients in the control group (P<0.001). This outcome was achieved before the initiation of cycle 2 in 43.4% (95% CI, 37.5 to 49.3) and in 7.6% (95% CI, 3.8 to 13.2), respectively (P<0.001). In the azacitidine plus venetoclax group versus the control group, the median time to first response (either complete remission or complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery) was 1.3 months (range from 0.6 to 9.9) and 2.8 months (range from 0.8 to 13.2), respectively; the median duration of composite complete remission was 17.5 months (95% CI, 13.6 to not reached [NR]) and 13.4 months (95% CI, 5.8 to 15.5), respectively; complete remission was 36.7% and 17.9%, respectively (P<0.001), and the duration of complete remission was 17.5 months (95% CI, 15.3 to NR) and 13.3 months (95% CI, 8.5 to 17.6), respectively.

Complete remission plus complete remission with partial hematologic recovery was achieved in 64.7% (95% CI, 58.8 to 70.2) of the patients in the azacitidine plus venetoclax group and in 22.8% (95% CI, 16.2 to 30.5) of those in the control group (P<0.001); this outcome was reached before the beginning of cycle 2 in 39.9% (95% CI, 34.1 to 45.8) and 5.5% (95% CI, 2.4 to 10.6), respectively (P<0.001). The median time to first response was 1.0 month (range from 0.6 to 14.3) and 2.6 months (range from 0.8 to 13.2), and the duration of response was 17.8 months (95% CI, 15.3 to NR) and 13.9 months (95% CI, 10.4 to 15.7), respectively. Red-cell transfusion independence occurred in 59.8% (95% CI, 53.9 to 65.5) of the patients in the azacitidine plus venetoclax group and in 35.2% (95% CI, 27.4 to 43.5) of the control group (P<0.001); and platelet transfusion independence occurred in 68.5% (95% CI, 62.8 to 73.9) and 49.7% (95% CI, 41.3 to 58.1) (P<0.001), respectively.

In patients who were treated with azacitidine plus venetoclax, as compared to azacitidine plus placebo, the median event-free survival was 9.8 months (95% CI, 8.4 to 11.8) and 7.0 months (95% CI, 5.6 to 9.5) with clinical significance (hazard ratio for death, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.50 to 0.80; P<0.001). In patients with composite complete remission who had measurable residual disease of less than 1 residual blast per 1000 leukocytes, overall survival at 24 months was 73.6% in the azacitidine plus venetoclax group and 63.6% in the control group.

In regarding to the analysis of the molecular subgroups, patients who were treated with azacitidine plus venetoclax showed a higher incidence of composite complete remission than those received azacitidine plus placebo. The incidence of composite remission, among those who received azacitidine plus venetoclax versus those in the control group, in those with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations, FLT3 mutations, NPM1 mutations, and TP53 mutations, were 75.4% (95% CI, 62.7 to 85.5) versus 10.7% (95% CI, 2.3 to 28.2) (P<0.001), 72.4% (95% CI, 52.8 to 87.3) versus 36.4% (95% CI, 17.2 to 59.3) (P = 0.02), 66.7% (95% CI, 46.0 to 83.5) versus 23.5% (95% CI, 6.8 to 49.9), (P = 0.012), and 55.3% (95% CI, 38.3 to 71.4) versus 0%, respectively (P<0.001). Lastly, in patients with composite complete remission, measurable residual disease negativity occurred in 23.4% (95% CI, 18.6 to 28.8) of the patients who received azacitidine plus venetoclax and in 7.6% (95% CI, 3.8 to 13.2) of those in the control group.

No differences between the two treatment groups with respect to the quality-of-life were seen.

Discussion

This phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial demonstrated that in previously untreated patients with AML who were ineligible for intensive induction chemotherapy, the treatment of azacitidine plus venetoclax, as compared with azacitidine plus placebo, showed more efficacy without added adverse effects. This was evident by the longer median overall survival, 14.7 months versus 9.6 months, the higher incidence of composite complete remission, 66.4% versus 28.3%, as well as the higher incidence of complete remission plus complete remission with partial hematologic recovery, 64.7% versus 22.8%, in patients received azacitidine plus venetoclax versus those in control group, respectively.

In addition, in those patients who had received azacitidine plus venetoclax, the median length of time it took to achieve both composite complete remission (either complete remission or complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery) and complete remission plus complete remission with partial hematologic recovery was shorter, 1.3 months and 1.0 month, respectively, as compared to those in the control group, 2.8 months and 2.6 months, respectively. The responses also last longer in those who received azacitidine plus venetoclax, as compared with those in the control group (17.5 months versus 13.4 months in regard to composite complete remission and 17.8 months versus 13.9 months in regard to complete remission plus complete remission with partial hematologic recovery).

With the advancement of clinical and translational research, we now run molecular profiling on all AML cases at the time of diagnoses as different mutations carry prognostic and therapeutic impact and dictate how we approach the treatment of AML. Knowing that the incidence of the composite remission of patients who received azacitidine plus venetoclax would be higher than those did not receive venetoclax, unrelated to their mutational status (IDH1 or IDH2, FLT3, NPM1, and TP53), would serve as an important guidance in terms of treatment strategy forward.

This study, however, has its own limitations. One of such is the exclusion of patients who had received any HMA, venetoclax, or chemotherapy previously. More studies need be done in this patient population in the future.

In conclusion, in previously untreated patients with AML who were ineligible for intensive induction chemotherapy, the treatment of azacitidine plus venetoclax, as compared with azacitidine alone, showed more efficacy without added adverse effects. The combination of azacitidine and venetoclax allowed for a longer median overall survival, a higher incidence of composite complete remission, as well as a more rapid and durable response, in this patient population.

| F: Follow up | 20.5 months |

| R: Randomization | Yes |

| I: Intention to treat | Yes |

| S: Similar at baseline | Yes |

| B: Blinding | Yes |

| E: Equal treatment | Not discussed |

| S: Source (funding) | AbbVie and Genentech |

References

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Acute Myeloid Leukemia (Version 2.2021). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/aml.pdf. Accessed June 7, 2021.

- National Cancer Institute. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2016. 2018. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016/ based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. Accessed June 7, 2021.

- Richard-Carpentier G, DiNardo CD. Venetoclax for the treatment of newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia in patients who are ineligible for intensive chemotherapy. Ther Adv Hematol 2019; 10:2040620719882822.

- Dombret H, Seymour JF, Butrym A, et al. International phase 3 study of azacitidine vs conventional care regimens in older patients with newly diagnosed AML with >30% blasts. Blood 2015;126:291-299.

- Konopleva M, Pollyea DA, Potluri J, et al. Efficacy and biological correlates of response in a phase II study of venetoclax monotherapy in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Discov 2016;6:1106-1117.

- DiNardo CD, Pratz KW, Letai A, et al. Safety and preliminary efficacy of venetoclax with decitabine or azacitidine in elderly patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukaemia: a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:216-228.