LEAP – Peanut Consumption for High-Risk Infants

Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy.

Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al.; LEAP Study Team

N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 26;372(9):803-13. [Full text, Video Summary]

Summary by Jennifer Haydek

The prevalence of peanut allergy has recently increased, nearly doubling in the 10 years prior to the publication of the LEAP trial. In the hope of preventing peanut allergy, clinical practice guidelines prior to the LEAP trial recommended total avoidance of peanut products for at-risk children and their mothers [1]. Yet it was noted that Jewish children in Israel had significantly lower rates of peanut allergy compared with Jewish children in the UK with the notable difference between the two being the age at which peanut products were introduced [2]. The hypothesis that early introduction of the peanut antigen might prevent development of peanut allergy in at risk children was assessed in the LEAP trial.

Patient population and Design

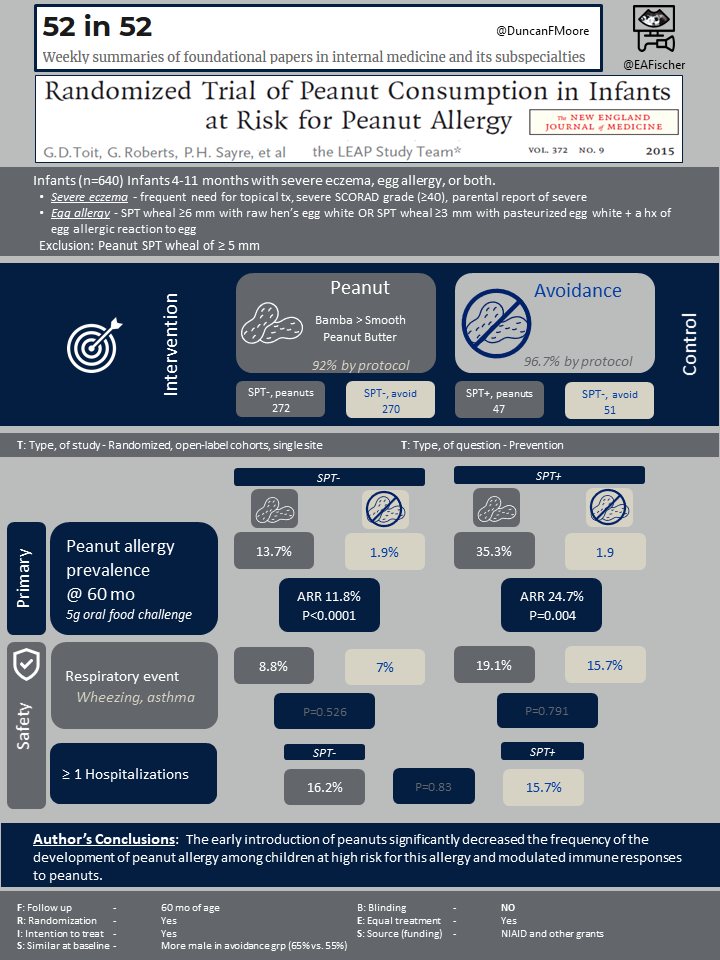

The study enrolled 640 infants between ages 4 months and 11 months who had severe eczema, egg allergy, or both, which had been previously identified as a useful in identifying intermediate risk of peanut sensitization [3]. Severe eczema was defined and egg allergy was identified as follows:

Severe eczema (any one)

- frequent need for topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors

- parental description of “a very bad rash in joints and creases” or “a very bad itchy, dry, oozing, or crusted rash,”

- severe SCORAD grade (≥40) by a clinician before or at the time of screening

Egg allergy

- SPT-induced wheal ≥6 mm with raw hen’s egg white

- SPT-induced wheal ≥3 mm with pasteurized hen’s egg white with a history of an allergic reaction to egg

These children subsequently underwent peanut skin-prick testing to establish preexisting sensitivity to peanut antigen. A subset of 98 children that developed a wheal 1-4mm wide after skin-prick testing (SPT) were assigned to one study cohort, the SPT-positive cohort. Any children who developed a wheal of ≥ 5 mm was excluded entirely. Within each study cohort, the participants were randomly assigned to either consistent weekly consumption of peanut or total avoidance of peanut until age 60 months.

The preferred peanut source was Bamba, a snack food manufactured from peanut butter and puffed maize. Smooth peanut butter was provided to infants who did not like Bamba.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was the prevalence of peanut allergy in each study group at age 60 months. Prevalence was assessed independently in the negative and positive skin-prick cohorts. At age 60 months, participants underwent an oral food challenge to determine the presence of peanut allergy. Safety outcomes for this trial included mortality and hospitalizations from any cause and prespecified serious adverse events.

Results

The median age at enrollment was 7.8 months. More males were randomly assigned to the avoidance group than to consumption (64.8% vs. 55.2%). The study had a 98.4% retention rate.

Within the cohort without preexisting peanut sensitivity, 13.7% of the peanut avoidance group had developed peanut allergy at 60 months of age compared with 1.9% of the peanut consumption group, with an absolute risk reduction of 11.8% (CI 3.4 to 20.3; P<0.001) and relative risk reduction of 86.1%. Within the cohort with initial peanut sensitivity, 35.3% of the peanut avoidance group and 10.6% of the peanut consumption participants had developed peanut allergy, with an absolute difference in risk of 24.7% (CI 4.9 to 43.3; P=0.004) and relative reduction in risk of 70.0%. No deaths occurred during the study, and there were no significant differences in hospitalization rates or rates of adverse events.

Discussion

The LEAP trial established that in children at high-risk for peanut allergy, consuming peanut products from an early age substantially reduces the risk for development of peanut allergy. This strategy is effective both as primary prevention in high-risk children without preexisting sensitivity and secondary prevention in individuals who are already sensitized. It should be noted the above conclusions do not apply to low-risk children (without an atopic predilection, such as severe eczema or known egg allergy) in whom any food tasting can be introduced without reservation when developmentally appropriate (actual food introduction requires adequate head control), typically 6 months [4].

This study was practice changing and was the first randomized trial to study early antigen introduction with the goal of allergy prevention. Prior to the study enrollment, clinical practice guidelines within the US and UK recommended total peanut avoidance in high-risk children and their mothers with the hope of allergy prevention. After the LEAP trial’s publication, a consensus guideline was published recommending the early introduction of peanuts in high-risk children [5] and in 2019 the AAP similarly updated their guidance [4]. The study investigators subsequently published a follow-up study LEAP-ON, establishing that the prevention of peanut allergy persists after 60 months, even if no peanuts are consumed for a year [6]. Ultimately, the LEAP trial changed the practice landscape around peanut allergy prevention with its robust findings that early introduction of peanuts in at-risk children is effective in preventing peanut allergy.

| F: Follow up | to 60 mo of age |

| R: Randomization | Initial stratification by presence of peanut sensitization and subsequent randomization into peanut consumption or peanut avoidance groups |

| I: Intention to treat | Yes |

| S: Similar at baseline | More male in avoidance group (64.8% vs. 55.2%) |

| B: Blinding | NO |

| E: Equal treatment | Yes |

| S: Source (funding) | National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and others |

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000 Aug;106(2 Pt 1):346-9. PMID: 10920165.

- Du Toit G, Katz Y, Sasieni P, Mesher D, Maleki SJ, Fisher HR, Fox AT, Turcanu V, Amir T, Zadik-Mnuhin G, Cohen A, Livne I, Lack G. Early consumption of peanuts in infancy is associated with a low prevalence of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Nov;122(5):984-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.039. PMID: 19000582.

- Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Plaut M, Bahnson HT, Mitchell H, Radulovic S, Chan S, Fox A, Turcanu V, Lack G; Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) Study Team. Identifying infants at high risk of peanut allergy: the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) screening study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Jan;131(1):135-43.e1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.09.015.

- Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW; COMMITTEE ON NUTRITION; SECTION ON ALLERGY AND IMMUNOLOGY. The Effects of Early Nutritional Interventions on the Development of Atopic Disease in Infants and Children: The Role of Maternal Dietary Restriction, Breastfeeding, Hydrolyzed Formulas, and Timing of Introduction of Allergenic Complementary Foods. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr;143(4):e20190281. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0281. Epub 2019 Mar 18. PMID: 30886111.

- Fleischer DM, Sicherer S, Greenhawt M, Campbell D, Chan E, Muraro A, Halken S, Katz Y, Ebisawa M, Eichenfield L, Sampson H, Lack G, Du Toit G, Roberts G, Bahnson H, Feeney M, Hourihane J, Spergel J, Young M, As’aad A, Allen K, Prescott S, Kapur S, Saito H, Agache I, Akdis CA, Arshad H, Beyer K, Dubois A, Eigenmann P, Fernandez-Rivas M, Grimshaw K, Hoffman-Sommergruber K, Host A, Lau S, O’Mahony L, Mills C, Papadopoulos N, Venter C, Agmon-Levin N, Kessel A, Antaya R, Drolet B, Rosenwasser L. Consensus Communication on Early Peanut Introduction and Prevention of Peanut Allergy in High-Risk Infants. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Jan-Feb;33(1):103-6. doi: 10.1111/pde.12685. Epub 2015 Sep 10. PMID: 26354148.

- Du Toit G, Sayre PH, Roberts G, Sever ML, Lawson K, Bahnson HT, Brough HA, Santos AF, Harris KM, Radulovic S, Basting M, Turcanu V, Plaut M, Lack G; Immune Tolerance Network LEAP-On Study Team. Effect of Avoidance on Peanut Allergy after Early Peanut Consumption. N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr 14;374(15):1435-43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514209. Epub 2016 Mar 4. PMID: 26942922.