Timing of Endoscopy for UGIB

Timing of Endoscopy for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Lau JYW, Yu Y, Tang RSY, et al.

N Engl J Med. 2020;382(14):1299-1308. [Full text]

Guidelines suggest that upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) should be endoscopically addressed within 24 hours after presentation [1]. While this has shown improved outcomes, this recommendation is mainly based on observational studies [2]. There have been small trials looking at endoscopy even sooner than 24 hours. For example. a study of 93 patients that underwent EGD prior to admission identified 40% who could be managed as an outpatient [3], but early endoscopy has not been shown to benefit hemodynamically stable patients in other outcomes [3, 4]. The current study by Lau et al. is a a large, randomized trial involving high-risk patients attempts to answer the question of early endoscopy.

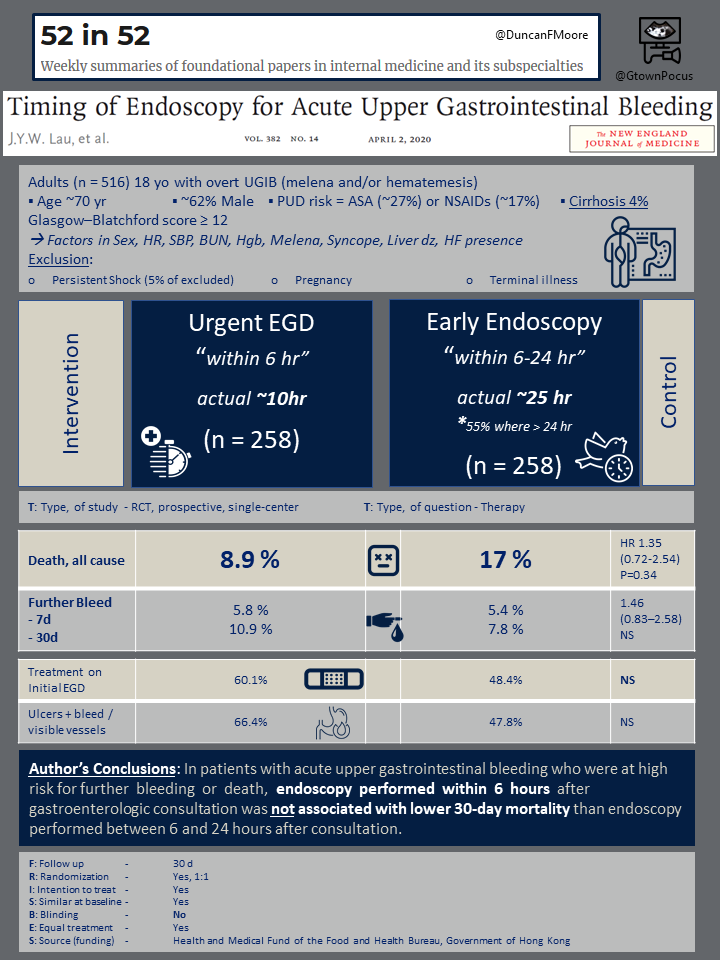

This study is a prospective, randomized, controlled trial at a single center that was designed to compare endoscopy within 6 hours of presentation vs. within 6 and 24 hours in high risk patients. The authors hypothesized that for patients at high risk of further bleeding and death, urgent endoscopy within 6 hours of presentation would reduce further bleeding and improve mortality.

Patient Population

A total of 516 patients were included in the study who had overt signs of acute UGIB (hematemesis, melena, or both) and either presented to the emergency department or were already admitted. Patients were screened using the Glasgow–Blatchford score (based on the SBP, HRm Hgb , BUN, melena or syncope, hepatic disease or cardiac failure). Patients who scored 12 or higher were eligible for enrollment. Notably, patients who were in hypotensive shock or whose condition did not stabilize after initial resuscitation were excluded from the study.

Results

The primary outcome was 30-day mortality from any cause. Secondary outcomes included receipt of endoscopic therapy at first endoscopy, further bleeding (defined as persistent or recurrent bleeding), duration of stay in the hospital and intensive care unit, receipt of further endoscopic treatment, emergency surgery or angiographic embolization to achieve hemostasis, blood transfusions, and adverse events within 30 days after randomization.

The source of bleeding was similar for both the urgent group (within 6 hours) and early group (between 6 and 24 hours) with peptic ulcer being most common (61.2% vs. 61.6%) and esophageal varices being second most common (9.7% vs. 7.3%). Given the delay from presentation to GI consultation, the actual mean time from presentation to endoscopy was 9.9±6.1 hours in the urgent group and 24.7±9.0 hours in the early group. 30-day mortality did not differ significantly between the two groups (8.9% vs. 6.6%, p=0.34). Further bleeding episodes within 30 days occurred in 10.9% of the urgent group and 7.8% of the early group. Endoscopic hemostatiswas performed on first endoscopy in 60.1% of patients in the urgent group vs. 48.4% of patients in the early group. Hospital and ICU stay did not differ significantly.

Discussion

Interestingly, the authors found that endoscopy performed within 6 hours (effectively 10 hr) did not lead to lower mortality or a lower incidence of further bleeding than if performed within 24 hours (effectively 25 hr). In the urgent group, more bleeding ulcers requiring more frequent endoscopic treatment; however, this did not result in decreased further bleeding or 30-day mortality. The longer period until endoscopy resulted in longer duration of PPI treatment and acid suppression, potentially leading to reduced number of ulcers with active bleeding; however, PPI prior to endocopy has not otherwise been shown to have a benefit on mortality or rebleeding [5].

The notable limitation of this trial is patients with persistent hypotensive shock despite resuscitation were excluded. Therefore, these results do not generalize to this population, and current guidelines still recommend urgent intervention in such patients [6].

Overall summary

This study showed that urgent endoscopy within 6 hours (10 hr observed) of presentation rather than early endoscopy between 6 and 24 hours (25 hr), did not result in a decrease in mortality for high risk but stable patients with acute upper GI bleeding. Rather the priority in the first 24 hours should remain resuscitation and treatment of any coexisting active medical conditions prior to EGD.

| F: Follow up | Yes, 30 d |

| R: Randomization | Yes, 1:! |

| I: Intention to treat | Yes |

| S: Similar at baseline | Yes |

| B: Blinding | No |

| E: Equal treatment | Yes |

| S: Source (funding) | Health and Medical Fund of the Food and Health Bureau, Government of Hong Kong |

Summary by Joseph Clinton

- Laine L. Timing of Endoscopy in Patients Hospitalized with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(14):1361-1363.

- Barkun AN, Almadi M, Kuipers EJ, et al. Management of Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Guideline Recommendations From the International Consensus Group. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(11):805-822.

- Bjorkman DJ, Zaman A, Fennerty MB, Lieberman D, Disario JA, Guest-Warnick G. Urgent vs. elective endoscopy for acute non-variceal upper-GI bleeding: an effectiveness study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60(1):1-8.

- Lin HJ, Wang K, Perng CL, et al. Early or delayed endoscopy for patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. A prospective randomized study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;22(4):267-271.

- Sreedharan A, Martin J, Leontiadis GI, et al. Proton pump inhibitor treatment initiated prior to endoscopic diagnosis in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(7):CD005415. Published 2010 Jul 7.

- Laine L, Jensen DM. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Mar;107(3):345-60; quiz 361.