SOME – Screening for Cancer After Unprovoked VTE

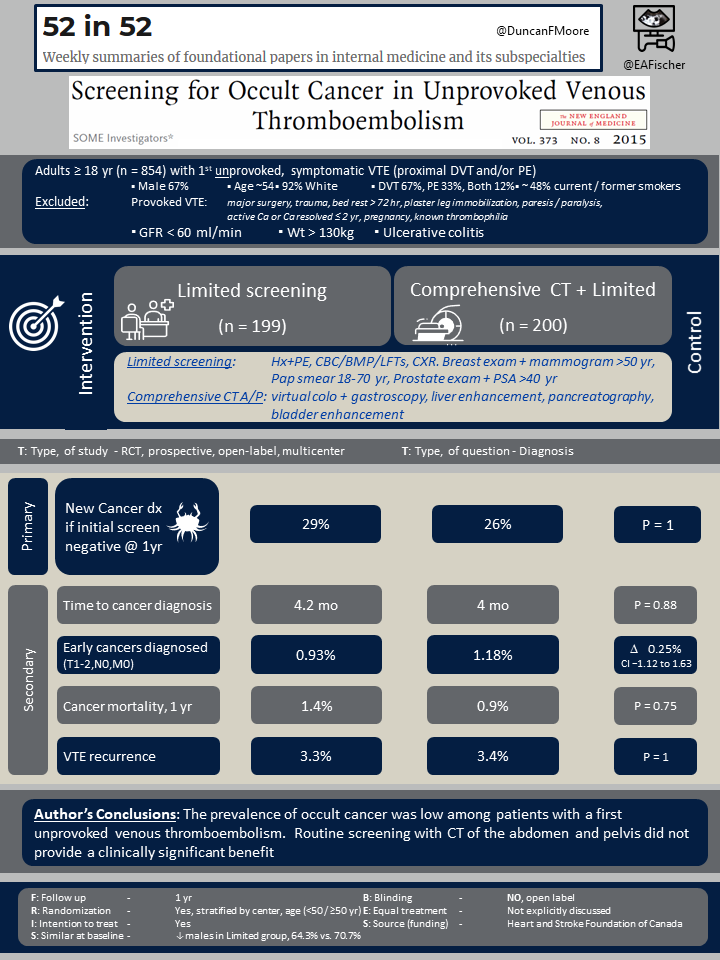

Screening for Occult Cancer in Unprovoked Venous Thromboembolism.

Carrier M, Lazo-Langner A, Shivakumar S, et al; SOME Investigators.

N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 20;373(8):697-704. [Full text]

Summary by Justin Yeh

The association of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and cancer is well known. With new VTE, in the absence of other provoking factors, occult cancer must always be considered. In fact, up to 10% of patients diagnosed with an unprovoked VTE will receive a diagnosis of cancer within 1 year [1]. Despite an increased risk, whether more extensive screening would benefit this population is a matter of some debate. While earlier identification of an occult cancer could theoretically improve outcomes, there would be concerns of incidental findings and other consequences of increased testing.

At the time of this study, there had been a lack of evidence to firmly guide screening decisions in patients with first-time unprovoked VTE [2]. The Screening for Occult Malignancy in Patients with Idiopathic Venous Thromboembolism (SOME) trial, a multicenter, randomized-clinical trial assessing the efficacy and safety of using CT of the abdomen and pelvis for extensive cancer screening, aimed to address this evidence gap.

Patient population and Design

Eligible adults were those with a new diagnosis of first-time, unprovoked, symptomatic VTE who were referred to one of nine participating Canadian centers in the study. Unprovoked VTE was defined as VTE in the absence of any of the following: overt active cancer, pregnancy, thrombophilia, a temporary predisposing factor within the previous 3 months (including paralysis, paresis, or plaster immobilization of legs) bedbound for 3 days or more, or major surgery. If any were present, a patient was excluded. Other exclusion criteria included contrast allergy, CrCl <60 mL/min, weight >130 kg, ulcerative colitis, or glaucoma. Those on hormonal therapy or smokers were notably not excluded.

The control arm of the study was a limited screening strategy, which included full history and physical exam, CBC, CMP, CXR, and sex-specific age-appropriate cancer screening for breast, cervical, and prostate cancer. The intervention arm extensive screening strategy included all of the limited screening strategy, along with comprehensive CT of the abdomen and pelvis (A/P). The CT A/P included virtual colonoscopy/gastroscopy, biphasic CT of the liver, parenchymal pancreatography, and uniphasic CT of the bladder.

The primary outcome was newly diagnosed cancer within one year of follow up after an initial negative screening. Data from patients with confirmed cancer on initial screen were censored. Secondary outcomes included number of occult cancers, number of early cancers, one year cancer-related mortality, 1-year overall mortality, time to cancer diagnosis, and recurrent VTE.

Results

Over the 5.5 year study period, 3186 patients were assessed for eligibility, and 862 underwent randomization. Of the patients included in the intention-to-test analysis, 67% were men, with a mean age was 54, and 93% were white. Of the patients 50 years or older, only 6.7% in the limited screening group and 10.2% in the extensive screening with CT group had undergone prior colon cancer screening.

A total of 14 patients in the limited screening group and 19 patients in the extensive screening group (limited + mulimodal CT A/P) received a diagnosis of occult cancer. For the primary outcome analysis, 4 of 14 cancers (29%; 95% CI, 8-58) were missed by limited screening, and 5 of 19 (26%; 95% CI, 9-51) were missed by extensive screening (P=1.0). The absolute rates of occult-cancer detection were 0.93% (95% CI, 0.36-2.36) and 1.18% (95% CI, -1.12 to 1.63) in the limited screening and extensive screening groups, respectively, with an absolute difference of 0.25%. There were no significant differences in secondary outcome analyses. No significant adverse events were reported with either strategy.

Discussion

The authors of the SOME trial concluded that CT A/P in addition to a limited screening strategy did not detect more occult cancers than limited screening alone. Using the best-case scenario results, the number needed to screen would be 91 in order to detect one missed cancer. In addition, screening with CT A/P did not reduce cancer-related or overall mortality at 1 year, time to cancer diagnosis, or incidence of recurrent VTE.

One of the major limitations of this study stems from the relatively few cases and low rate of malignancy detected in this study (3.9% within 1 year), possibly due to the younger population (mean age 54). This lower than expected rate likely reduced the power of the study to detect significant differences in cancer-screening strategies, if present. Another consideration is whether CT A/P was a preferred test for the extensive screening strategy. CT of the chest was not included in the screening strategy, as many patients had already undergone CT pulmonary angiography, and the authors felt that re-exposure to additional radiation for only study purposes was not reasonable. More extensive screening, such as with tumor markers or FDG PET/CT, may be more sensitive in detecting occult cancers.

Of note, only about 8% of patients 50 years and older in this study had received colon-cancer screening. Age appropriate colon cancer screening was not included in the limited screening strategy. Zero patients with colon cancer were detected in the limited screening strategy, as opposed to 3 in the CT A/P + limited screening group, which included virtual colonoscopy. Had the authors included colon cancer screening in the limited screening group, the results likely would have likely further reinforced that there was no difference between the two strategies.

Despite its limitations, the SOME trial remains the largest RCT in evaluating a limited versus extensive screening strategy for malignancy in unprovoked VTE. In part based on these data and subsequent studies, current guidelines recommend against extensive screening, in the absence of other risk factors, in this setting [3-5]. Instead, age-appropriate cancer screening, full history and physical exam, and basic laboratory testing are the standard of care.

There are exciting ongoing studies that attempt to address questions left unanswered by the SOME trial, particularly whether certain subgroups at higher risk could benefit from cancer screening as well as an optimal screening modality [6]. SOME RIETE is an RCT that uses the proposed RIETE score to risk stratify patients for occult cancer, with high-risk patients randomized to limited screening or limited screening + PET/CT. MVTEP2-SOME2 is an RCT evaluating FDG PET/CT as an extensive screening strategy in patients over 50.

| F: Follow up | 1 year |

| R: Randomization | Blocks of 2-4, stratified by center and age (<50 or ≥50 yo, i.e. for cancer risk) |

| I: Intention to treat | Yes |

| S: Similar at baseline | Less males in limited only group, 64.3% vs. 70.7% |

| B: Blinding | NO |

| E: Equal treatment | Not explicitly discussed |

| S: Source (funding) | Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada |

- Carrier M, Le Gal G, Wells PS, Fergusson D, Ramsay T, Rodger MA. Systematic review: the Trousseau syndrome revisited: should we screen extensively for cancer in patients with venous thromboembolism? Ann Intern Med. Sep 02 2008;149(5):323-33. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00007

- Robertson L, Yeoh SE, Stansby G, Agarwal R. Effect of testing for cancer on cancer- and venous thromboembolism (VTE)-related mortality and morbidity in patients with unprovoked VTE. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Mar 06 2015;(3):CD010837. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010837.pub2

- Delluc A, Antic D, Lecumberri R, Ay C, Meyer G, Carrier M. Occult cancer screening in patients with venous thromboembolism: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 10 2017;15(10):2076-2079. doi:10.1111/jth.13791

- van Es N, Le Gal G, Otten HM, et al. Screening for Occult Cancer in Patients With Unprovoked Venous Thromboembolism: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Individual Patient Data. Ann Intern Med. Sep 19 2017;167(6):410-417. doi:10.7326/M17-0868

- Robin P, Le Roux PY, Planquette B, et al. Limited screening with versus without (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT for occult malignancy in unprovoked venous thromboembolism: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. Feb 2016;17(2):193-199. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00480-5

- Marín-Romero S, Jara-Palomares L. Screening for occult cancer: where are we in 2020? Thromb Res. 07 2020;191 Suppl 1:S12-S16. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(20)30390-X